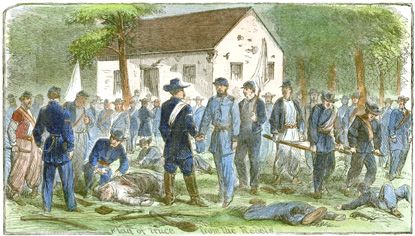

Battle of Antietam: The white German Baptist Church is visible in the background in this 1887 painting called "Battle of Antietam" by Thure de Thulstrup

In and around the yard of a pacifist Baptist church, the bloodiest one day battle in American history unfolds today: the Battle of Antietam.

Built in 1852 by German Baptist farmers, the Dunker Church on a hill near Sharpsburg, Maryland houses a peace-loving congregation of six to eight farm families. There is nothing peaceful about this day, however. Cannon fire had first been heard three days ago, while the Baptists worshiped on the Sabbath morning. The sounds were from the Battle of South Mountain, seven miles distant.

The far off but too-near sounds of battle on the Lord’s Day had signaled the approach of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. In an effort to put the United States on the defensive militarily, capture much-needed supplies, foment political unrest in the North, and perhaps bring Maryland into the Confederacy, Lee’s army had been conducting raids in northern territory. But on Sunday, Lee’s advance northward had finally been repulsed by U.S. General George B. McClellan. The battle had not been an overwhelming defeat for Lee, but it did check his momentum, and the great general momentarily considered turning back southward.

But turn back Lee did not, and on the sixteenth, yesterday, Confederate infantry and artillery had converged on the little Baptist church building. Anticipation and fear hung thick in the air. McClellan, in pursuit of Lee, had been reinforcing his army since the engagement at South Mountain. Lee was making his stand upon the high ground surrounding the little church.

This day dawns shrouded in fog. In the murkiness, a chorus of rifle fire begins. Over the next seven hours, Union forces thrice attack the entrenched Confederate forces. Stretched but not broken, the Confederate lines hold their ground. Near the end of the day, the armies disengage, rifle and cannon fire fall silent, and a truce is called. The casualties are epic: of the 100,000 soldiers engaged in war this day, 23,000–nearly one in four–are either dead, wounded or missing. Of those, 2,100 Union soldiers are dead, and 1,550 Confederate soldiers rise no more.

The Confederate Army turns the German Baptist church into a hospital. The morrow is a day for both armies to gather their wounded and bury their dead. That evening, Lee withdraws his army across the Potomac River and begins the march back to Virginia.

Lee’s retreat gives McClellan the victory, and lifts the hopes of the Northern public. Just as importantly, the successful repulsion of the Rebel invaders provides U. S. President Abraham Lincoln the public good will necessary to announce his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation–long contemplated–on September 22.

Lee’s Northern invasion, rather than boosting the prospects of the South, thus shifts momentum to the North and sets the stage for the biggest blow yet to southern African slavery.

Upon the departure of the armies, the German Baptist church is left riddled with bullet holes and damaged by cannon fire, war having left its mark upon the pacifist place of worship. Yet within two years, the church building is repaired and in use again, while the war slowly winds down in the face of dwindling Southern military power and diminishing public morale.

Sources: Battle of South Mountain (link); Battle of Antietam (link); “The Dunker Church: Antietam National Battlefield (link); “The Battle of Antietam: The Dunker Church” (link); Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation (link); Battlefield painting (link); Truce painting (link)