Spring may have officially arrived, but the occasional winter battle continues, sometimes in rather unexpected fashion. Today is one of those days.

Spring may have officially arrived, but the occasional winter battle continues, sometimes in rather unexpected fashion. Today is one of those days.

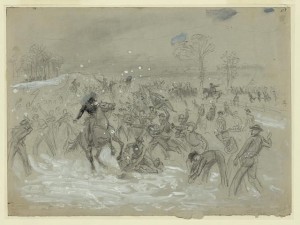

This morning near Dalton, Georgia the winter weather leads to a spirited battle. Troops from Arkansas in the Army of Tennessee seize the initiative when Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, the highest-ranking Irish-born officer in American military history, orders a surprise offensive early in the morning. The attack comes before breakfast, catching the defenders entirely unprepared.

A melee ensues in which Cleburne is captured, negotiates a quick release, is captured yet again, and released yet again … all in one day, the first day of what proves to be a ten day campaign.

From the beginning, this battle of Dalton is a spine-tingling affair in which cooler heads fail to prevail. Projectiles hurl through the air, followed by close, hand-to-hand combat. Blood stains the new fallen snow, one witness recounts. One veteran later commented, “The noise was terrific and the excitement intense.” Another claims of the battle that there was “nothing like it in the history of the world.”

When the day’s action ends, a relieved Cleburne, eying his opponents across the frozen divide, orders a round of whiskey for soldiers on both sides. Lubricated by drink, a celebration ensues, including yelling “at the top of their lungs.”

Thus ends the first campaign of the “Great Snowbattle of 1864.”

The snowstorm lasts for many days, and the snowball fights continue through the rest of the month. Descriptions of the fighting are vivid. “Such pounding and thumping, and rolling over in the snow, and washing of faces and cramming snow in mouths and in ears and mixing up in great wriggling piles together,” noted one soldier.

Baptists of the South have a (well-deserved) reputation for frowning on fun, evidenced in Baptist newspapers and church records that proclaim dancing, cards, theater, music, sports (including baseball or base-ball) and other forms of recreation and leisure as sinful behavior deserving of censure. But snow ball fights? Odds are that a few Baptist soldiers who witness the days events do so with a frown, perhaps wagging a finger at their fellow soldiers who suffer bloodied noses from well-thrown chunks of ice-packed snow. But, hopefully, perhaps some Baptists do take part in the fun, sin be damned.

Later in the day, a soldier from Mississippi writes of the action and shifting loyalties that take place among snowball-armed regiments of Mississippians, Alabamians, Louisianans and Kentuckians during the great snow battle:

Camp Stanford’s Battery, Near Dalton, GA, March 22

Our optics opened wild with astonishment this morning, when we peeped out from our “shanty” and saw mother earth’s bosom covered with a snowy mantle, four or five inches thick. As soon as we had gotten our “grub,” we were ready for fun, and immediately the boys of our battery engaged in an indiscriminate snow-balling frolic.

Pretty soon, word came to us that the Eufaula battery was preparing to engage us, and feeling the honor of Mississippi was at stake, we formed in line of battle and met the Alabama boys on the line that divides our camps. Here we had a spirited engagement for fifteen minutes or more, when hostilities ceased; and as neither party could claim the victory, we formed an alliance, offensive and defensive, and proceeded to charge Fenner’s Louisiana battery, also in our battalion. The gallant Louisiana boys feeling that it was a point of honor for them to protect their territory from invasion, turned out en masse, and having advantage of position, withstood all our assaults. They held a gap on the hillside, and as their flank were protected by a thicket of bushes, we could gain but little ground.The battle had been raging for half an hour with alternate success, when, looking down the road in our rear, we saw two regiments of infantry (the 16th and 25th Louisiana I believe), approaching us rapidly and fully armed for the fray. They came over for the purpose of whipping out Fenner’s battery. As soon as we learned this, we immediately struck hands with our late antagonists, and all the batteries now united, we marched to meet the common foe. The conflict was a desperate one, as we were determined to drive the invaders from our camps. The enemy’s battle-flag, an old silk handkerchief tied to a pole, advanced near our lines, when some of our gallant boys made a charge, and after a hard struggle, effected its capture. At length, after many hard blows on either side, the enemy sent forward a flag of truce, when hostilities ceased, and another alliance was formed. The officer commanding the infantry detachment then proposed to take his regiments and the remainder of his brigade (Gibson’s Louisiana brigade), and with the aid of our artillery battalion, commanded by Maj. Eldridge, we would, altogether, make an attack upon Bate’s old brigade, encamped about a mile distant.

The proposition was agreed to–we soon formed all our companies and regiments, and tramped through the deep snow to the enemy’s camp; when near it we formed in line of battle and deployed skirmishers in front. We found the foe fully prepared to meet us. They were drawn up in line, with their colors flying to the breeze. Our skirmishers now advanced and drove in those of the enemy. Our whole line followed in a tremendous charge, cheering and yelling, while our officers gallantly led us on. The first charge broke the lines of the enemy, and we followed them to their camps, capturing a battle flag and several prisoners. They soon rallied, however, and rushed on our left flank with so much impetuosity that our ranks were broken, and another Missionary Ridge scene was enacted. The victorious enemy pelted us severely, and pursued our routed columns, taking many prisoners. I had the honor of bearing one of our standards–the aforesaid pocket handkerchief we captured on the occasion. While I was “changing my base,” a tall, daring fellow from the enemy’s lines rushed forward, overtook me, and seized my flag; about a dozen others ran up to his assistance, and in spite of my valorous struggle, and shouts for help, they took me off a prisoner, and secured the captured colors. From that time I was only a spectator. More stirring scenes were to be enacted. Heavy reinforcements now came to the relief of our scattered brigade and battalions. Clayton’s, Stovall’s and Baker’s brigades, all of Stewart’s division, were seen advancing. Two long lines of battle were formed–our routed columns again restored to order, and the command forward was given, which was followed by a yell that would have done credit to a legion of Camanches [sic]. Bate’s old brigade had also been reinforced, as I was informed, by the Kentucky brigade, General Lewis, and perhaps others. The charge was sounded by our buglers, and the brigadiers and colonels gallantly led on their respective commands. When the contending columns met, the shock was terrible–the air was filled with whizzing snowballs, and above the confusion rung out on the clear cold air the shouts of the combatants. Here and there might be seen some unlucky hero placed hors du combat, with a red eye or a bloody nose. Field officers seemed to be the most desirable game, and many a major, colonel and brigadier was soundly pelted, and in some cases captured, horse, equipments and all. Our column, heavily reinforced as it was, proved too much for Bate’s division. The enemy’s ranks were broken; and our now victorious braves drove them into their camps, where they were glad of the opportunity to take shelter in their cabins.

We captured several battle flags and a number of prisoners. But our victory was dearly bought. We lost two or three standards, and have to mourn the loss of many gallant officers and men. Major Eldridge commanding our battalion was captured in the first charge; also, Adjutant Colwell, commanding the Eufaula artillery. Time and space fail to tell of all the gallant deeds performed by our braves. The enemy being routed in the last charge, our scattered forces were collected, and the victorious host marched back to camps, every man well tired, well bruised, but with all in good humor, each one feeling himself a hero. The snow continued to fall during the day and attained to the depth of six inches. Our army here is in splendid fighting trim. Full confidence is felt in our gallant commander. The troops are in good spirits, and their physical condition unsurpassed. If the Yankee host of Thomas see fit to try our mettle, they will find us ready, and will assuredly meet with something warmer than a snowball reception.

Sources: William C. Davis, Russ A. Pritchard, Fighting Men of the Civil War, University of Oklahoma Press, 1998, p. 150 (link); “Snow Fights in the Army,” Charleston Mercury, March 31, 1864 (link); “Patrick Ronayne Cleburne (1828–1864),” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (link); “Rebel and Yank Snowball Wars: Fighting Winter Boredom,” Civil War Stories of Inspiration (link); “Program on Dalton’s Great Snowball Battle of 1864 is March 22,” The Chattanoogan (link); Mills Lane (ed.), “Dear Mother: Don’t grieve about me. If I get killed, I’ll only be dead.”: Letters from Georgia Soldiers in the Civil War (Savannah: Beehive Press, 1990), p. 285, quoted in “This Week in Georgia Civil War History” (link); “The snowball battle near Dalton, Georgia,” Library of Congress, including image (link)